Why Box-Toppers?

When I was a kid watching the baseball game of the week on TV (we only had one game a week on TV back then), the announcer would invariably name a Player of the Game at the end of the telecast.

Sometimes they chose the player who hit the winning home run in the bottom of the ninth, even though he may have struck out in three other at-bats. Granted, the team wouldn’t have won the game without his contribution. But what about his teammate who went 3-for-4, drove in two and scored three runs? And what about his team’s pitcher who threw seven scoreless innings, striking out five and walking none, only to have a reliever come in and give up the lead in the eighth? It seemed to me that in some cases, the announcers were either being short-sighted or so swayed by the drama of a flashy play that they forgot who really contributed most to the win. But all they had to do was to look at the box score.

The Box-Toppers metric gives credit to the player whose contribution—according to the box score—played the biggest factor in that team’s victory. In this example game, the seven-scoreless-inning pitcher was likely the top player in the game by Box-Toppers standards (even though in the actual game, he was not even eligible for the win).

Further, as the season progressed and discussion moved to who was deserving of postseason best-player awards, the talk sometimes seemed (and seems) too driven by emotion, trumped-up and bally-hooed trends and other irrelevant information. Many times, the player on an August or September hot streak is touted for MVP or Cy Young awards while another player’s solid, steady performances often from early in the season—which did just as much to contribute to a team’s win-loss percentage—are overlooked.

Box-Toppers takes a longer view, taking the entire game into account and taking the entire season into account, too. It not only measures which player contributed most to each win, but can determine which players contributed most to his team’s overall wins. Since a player’s Box-Toppers point total is accumulated through the season, the metric offers a data point which can be used to directly compare the performances of players with each other.

•

I began the Box-Toppers website in 2013.

I began systematically tracking box scores with this simple, odd-seeming set of formulas in 1994. Why? I felt out of touch with baseball. It had been a childhood passion for my brother and me. Though neither of us were great baseball players (I was awful, Andy was decent), we collected baseball cards and eagerly anticipated the arrival of The Sporting News, the national sports tabloid weekly. Though it was nearly a week out of date by the time we received it, we pored over its standings and box scores and player statistics charts until our hands were coated in newsprint ink so thick we didn’t need to use pine tar to improve the grip on our bats.

During the strike of 1981, I lost touch with baseball. I stopped collecting baseball cards. Somewhere along the way, my Sporting News subscription lapsed. I barely noticed when my formerly beloved Kansas City Royals finally won the World Series in 1985. I tuned in now and again mainly during the postseason, but I found myself complaining about how boring the game had become.

It was odd that a strike in 1981 had pulled me out of baseball because it was the strike in 1994—the one that prematurely ended the season and caused the postseason playoffs and World Series to be cancelled—that brought me back to the game.

In 1995, when baseball finally resumed, I was eager for play to begin. But since I had not been following the game closely for more than a decade, I really didn’t know the players or the teams very well anymore. I didn’t feel I had the time to know the players as I had when I was a kid—poring over newspaper box scores and reading the backs of their baseball cards. I needed a shortcut.

So each day, I skimmed the box scores to find the player in each game who contributed most to his team’s win. That was interesting. But then I decided I needed to track these players, so I could determine which player contributed most to his team’s total victories over the season. I devised a simple database in a now-defunct program called AppleWorks and spent a few minutes a day examining the data from my local newspaper (this was still really before any sort of useful internet) and compiling it in the database. (Here is a post from April 25, 2020, marking the 25th anniversary of the first game tracked by Box-Toppers, played on April 25, 1995.)

These few minutes a day helped reconnect me with the game. I discovered the players who were the stars of the game. I was able to spot the up-and-coming rookies. Overall, I felt I knew the players and the character of the teams.

Gradually, systems became slightly more sophisticated. Software improved. The internet developed. And in 2013, Box-Toppers.com was launched as a way to share the player tracking system more widely.

Over 25 seasons, Box-Toppers has examined more than 60,000 regular season games, determining a Player of the Game in each, and has tracked entire careers of baseball players, including tracking the first from rookie season to Hall of Fame induction—Vladimir Guerrero, who played from 1996 to 2011 and was inducted in 2018.

Dedication

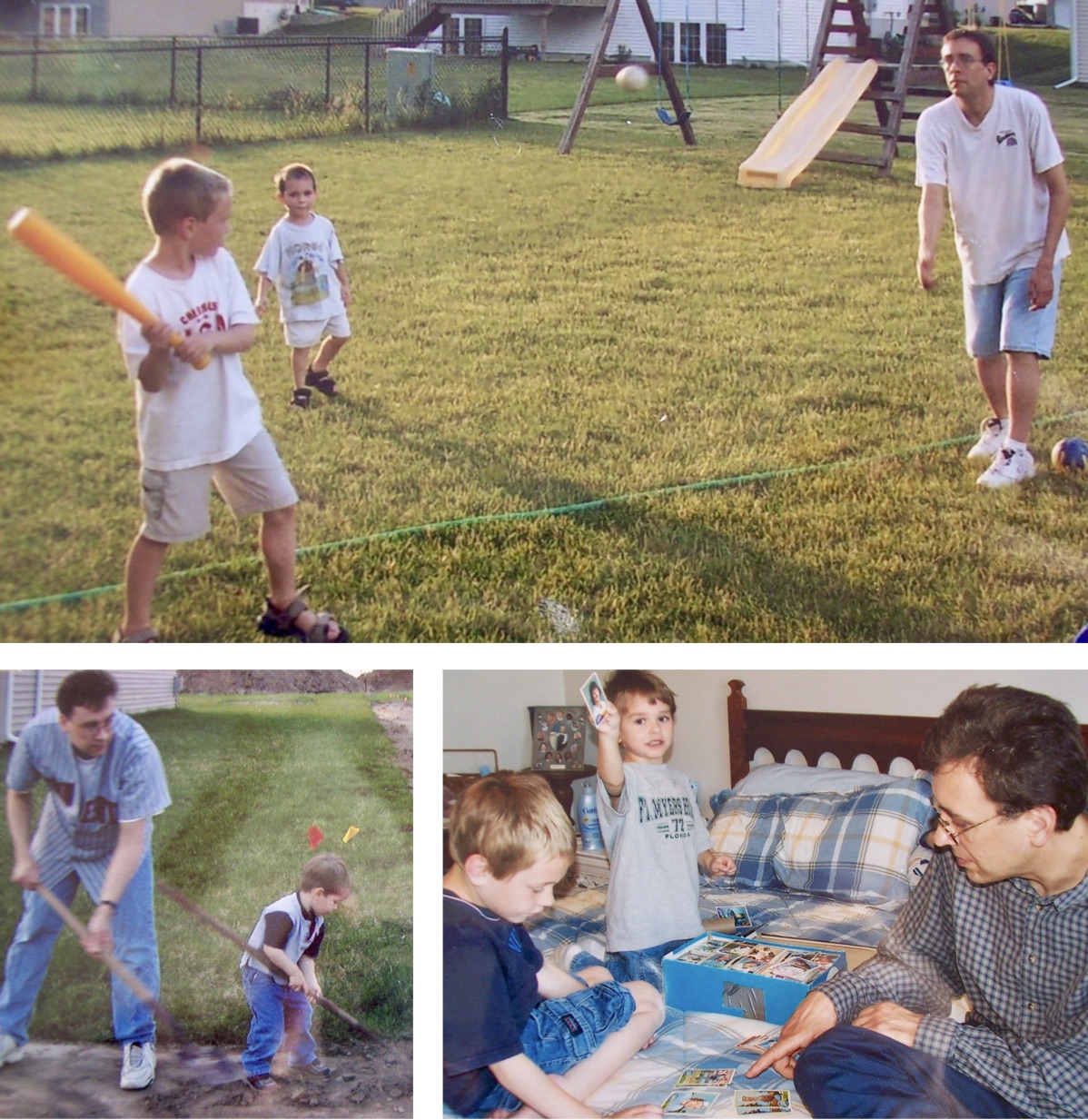

My brother Andy playing baseball with his two young sons, working in the yard wearing his Johan Santana jersey and showing them the baseball cards he collected from the time Andy and I were kids their age.

This website, this baseball project is dedicated to the memory of my brother Andy Plank, a lifelong baseball fan.

Growing up, we shared a love of the game. In the 1970s and 1980s, his favorite team was the Los Angeles Dodgers and his favorite player was All-Star first baseman Steve Garvey. In the 2000s, when his attention shifted to fantasy baseball, he always made sure he had Minnesota Twins pitcher Johan Santana on his team, helping to rack up fantasy points.

In 2005, Andy was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS is an invariably fatal neurological disease that causes muscle wasting and eventual death by respiratory failure within two to five years of diagnosis. It is popularly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, named for the Yankees baseball player whose career was ended by ALS. Gehrig was diagnosed in 1939 and died in 1941.

It goes without saying that is sadly ironic that Andy, a big baseball enthusiast, was stricken with the disease named for a baseball player. When he was diagnosed, we seriously put our hopes on him having another eponymously named disease, like Parkinson’s—still terrible but way less terrible than ALS. We wished his prognosis could be improved with a medical procedure named for another baseball player. But Tommy John surgery was of no use.

Andy lived nearly five years after his diagnosis.

At his funeral, his wife and two young sons acknowledged his love of the game. As mourners entered the service, they were each handed a baseball card—mine was a 2010 Topps card of Ryan Howard of the Phillies. Atop his casket, among other baseball memorabilia, was his prized Johan Santana jersey and his 1971 Topps baseball card of Steve Garvey.

NEW: Inbox notification of each post!

NEW: Inbox notification of each post!